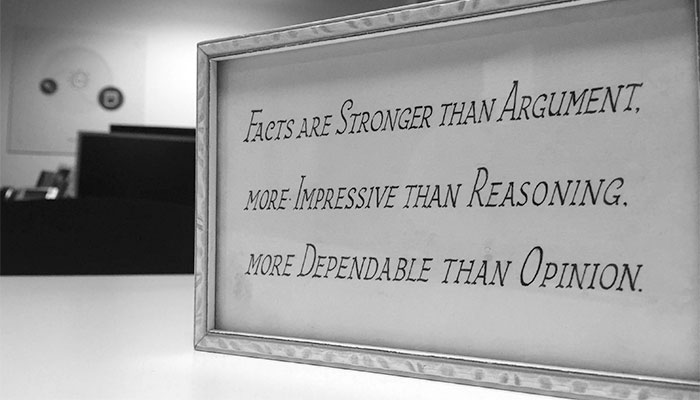

One of the odd little things that reminds me of my Dad currently sits in a small, unkempt frame on my desk.

It’s an obscure quote that I’ve traced to a U.S. congressional hearing on air safety, of all things. However it made its way in front of Dad, it was clearly something that resonated with him enough to frame it, and is nicely evocative of the man. It reads:

“Facts are stronger than argument, more impressive than reasoning, more dependable than opinion.”

My father was a pragmatist, although I suspect he wouldn’t have labelled himself such. He valued honesty, plain speaking, and facts; something I hope I’ve inherited an amount of from him.

I often attempt to mirror my own profession with his, trying to convince myself that his highly practical skills (Dad trained as a joiner) are somehow mirrored in my distinctly soft skill-set. That said the principles of craftsmanship regularly feature in the challenges I find myself involved with daily.

‘Measure twice and cut once’ was one of his maxims, as it is for so many trades. The same advice is perfectly applicable to my own work, where it is imperative to question assumptions, to research, then – and only then – to begin designing a solution. Measure twice, cut once indeed.

Research can often be misconstrued as overly academic, a noble pursuit that gets in the way of practical action (if you pay close attention to some of the small print flashed on-screen in the middle of ads for hair or beauty products and you could lose faith in it altogether). But research shouldn’t hinder action. It can in fact act as a springboard to set a project off at a canter in the right direction, providing sufficient evidence that – in the words of Lean methodology – we are ‘building the right thing’.

Steve Blank, one of the founders of the Lean Startup movement, purports that “there are no facts inside your building” meaning that views from internal stakeholders alone can’t be taken as reflecting reality.

The role of research in design should be to deal with facts, to uncover truth and reflect it back at the organisation. Very often truth can be uncomfortable to stomach of course. Facts around poor conversion rates, low customer satisfaction ratings, low usability test scores and more can all be swept under the carpet because they are just too painful. Regardless of what the facts might be, they must be acknowledged and understood before something better can be achieved.

All views within a business or organisation are perfectly valid. They are also just pieces of a broader puzzle, one that can only be completed when those outside the building – specifically customers – get to add their voice to the mix. Research what any organisation represents to those customers and end users, and a very different picture can emerge to that which exists internally. It is likely to be a more definitive one.

The framed quote that sits on my desk is a paean to critical thinking, an approach that has been defined as “disciplined thinking that is clear, rational, open-minded, and informed by evidence” – exactly the space that user-centred design operates in.

In any discussion around what customers or users want, or what they need, there will be plenty of arguments, lots of reasoning, and no shortage of opinion. Greater than all of those are facts.

I won’t be taking that quote off my desk any time soon.